|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

He had done it. Rex leaned back in his Eames recliner, smugly reading over his “test plan” for the future with Frank’s access to the Stitcher organization. It was so clever he couldn’t stop smiling while flipping through the pages and charts. There was just one problem. He had to ensure that it didn’t fall into anyone else’s hands, and if it did, that it wouldn’t make any sense to them.

The plan, at its core, was playing the stock market, systematically, with some variance built in to throw off anyone or anything casually tracking the market. Knowing what they knew, about the AI warning Frank of “bad moves”, it was just a matter of placing the bets and raking in the profits, with an intentional loss from time to time of a few million credits. That would help throw off tracking, as well as serve as a tax shelter from a great deal of profit. Frank and Rex had already performed second-stage testing, to see if the AI could predict short-term losses through a tangle of shell corporations that Frank operated. The results didn’t surprise either of them: 100% success.

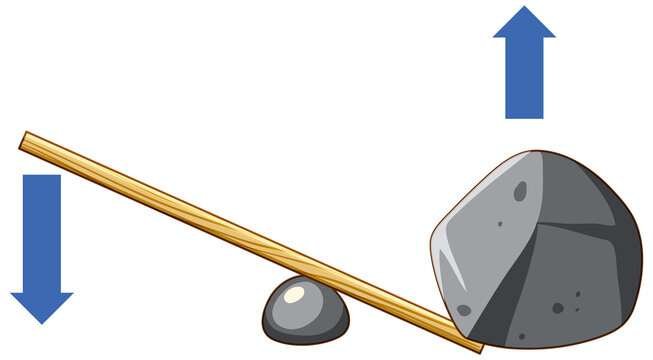

Rex dubbed his plan Project Fulcrum, because it gave him the leverage he needed, financially, to complete his own bigger project, without involving shadowy figures that deliver physical violence in the event of a late or missed payment. As far as he was concerned, there were no downsides. Frank and Rex would beat the casino on a regular basis, and eventually Rex’s project would be flush with cash and run to completion. He was reviewing and re-reviewing the plan to ensure that there were no dangling threads. It seemed airtight.

Back to the problem at hand. How to essentially encrypt the plan documents so that they only made sense to he and Frank. Distributing the plan piece by piece was a good start. Embedding those chunks into some other kind of data was another good idea. But reassembling the chunks in the right order was the absolute key to it all, and deserved the most consideration. For this, Rex turned to a DNA lab he had done business with, many years ago. They could create and assemble specific DNA strands to any specification, from nothing; you supplied the code. They could also embed that DNA into other, common strands, and you had to know the specific marker in the sequence to even begin to decode the DNA they had inserted. They would hide their strands specifically in DNA strands where variation was expected to be present; for example, the DNA sequence that determines the pattern of a leopard’s spots. No two were alike, and their location varied, as other sequences in the DNA would essentially point to wherever that gene sequence was located, which was also variable. There were also inactive genes one could hide new sequences, that functionally, did nothing in an organism. Fun fact, most human DNA is inactive, or copies of active sequences, which is why, once the human genome was 100% mapped out, they only found a 2% difference between humans and chimpanzees. In the programming world, this is known as cruft. Layer after layer of band aid coding that accumulated over the evolution of a species, or computer program. Eventually it led to bloat with genomes that were much longer than they actually needed to be, which again was beneficial for anyone trying to hide information in DNA.

Rex would eventually end up visiting the DNA lab, Blue Genes, and coding his creation. It would be an organism. It would grow and change over time. At regular steps of the organism’s growth cycle, it would shed and provide a new piece of the DNA puzzle to the recipient. The initial phase of life, the adjusted sperm and egg, would contain two keys to the DNA sequence lock. They were complimentary and mostly matching.

Rex was creating a snake. From birth, it would continually be fed and nurtured to reach the next growth phase. Once it was fully grown, sampling each of the shed skins would yield the entire plan for Project Fulcrum, so this would take some time. However, they could always accelerate the growth cycle from the beginning by tweaking some growth genes. It just meant that the snake wouldn’t live a long life, but the tradeoff was acceptable. This wasn’t a pet; it was a delivery system. Once the credits were transferred, Blue Genes would create the snake and hand it off to Rex in a plain cardboard box, which he would then hand-deliver to Frank. The instructions were nice and vague. “Here’s your pet snake. Keep him warm and fed, and clean his cage regularly”. Of course, cleaning his cage included carefully collecting pieces of the shed skin, and sending samples back to Blue Genes for analysis, decrypting the next piece of Project Fulcrum. But what about the sequencing numbers that tied it all together? Rex decided he’d deliver those to Frank, as needed, rather than handing them off up front. That would also add an element of randomness to the process to further prevent any kind of casual analysis in case anyone got curious. So that settled it, the plan for delivering the plan was another stroke of Rex genius. Frank just had to keep the snake alive, and with a small army of house staff at his disposal, assigning someone to take great care of his new pet was no more difficult than throwing darts at a target.

Well I didnt see that coming. Good explaination of DNA and using a snake that sheds, very clever. Im enjoying wondering where these last two are leading👍🏼😁.